On September 23, 2000, Alexander Fiseisky will perform the entire organ works of J.S. Bach in one day. See the program, stoplist, and Alexander’s bio here in both English and German.

Program 1 | Program 2 | Program 3 | Program 4 | Program 5 | Program 6 | Program 7 | Program 8 | Program 9 | Program 10 | Program 11 | Program 12 | Program 13 | Program 13 | Program 14 | Program 15 | Program 16

Organ and Stoplist of St Margareta Basilica | Alexander Fiseisky’s biography | About this performance

More about Alexander Fiseisky

Gesamte Orgelwerke / The Complete Organ Works

anläßlich des 250. Todestages von Johann Sebastian Bach /

In Commemoration of the 250-th Anniversary of the Death of Johann Sebastian Bach

gespielt von / played by Alexander Fiseisky

an der/on the Rieger-Organ

In tiefer Verehrung und zur Erinnerung an den größten Komponisten des letzten Jahrtausends

In profound honour and remembrance of the greatest composer of the second millennium

Program 1: 6.30 Uhr

Präludium und Fuge C-Dur, BWV 545

Choralbearbeitungen:

Valet will ich dir geben, BWV 735

Christ lag in Todesbanden, BWV 718

Präludium und Fuge g-Moll, BWV 535

Trio-Sonate e-Moll, BWV 528

Adagio. Vivace

Andante

Un poco Allegro

Choralbearbeitungen: Lobt Gott, ihr Christen, allzugleich, BWV 732

Jesu, meine Freude, BWV 713

Liebster Jesu, wir sind hier, BWV 706

Allein Gott in der Höh’ sei Ehr’, BWV 711

Herzlich tut mich verlangen, BWV 727

Präludium und Fuge c-Moll, BWV 546

Präludium und Fuge d-Moll, BWV 539

Choralpartita “Sei gegrüßet, Jesu gütig”, BWV 768

top of pageProgram 2:

8.00 Uhr

Präludium und Fuge C-Dur, BWV 531

Choralbearbeitungen:

Valet will ich dir geben, BWV 736

Gottes Sohn ist kommen, BWV 703

Liebster Jesu, wir sind hier, BWV 730

Christ lag in Todesbanden, BWV 695

Wer nur den lieben Gott läßt walten, BWV 690

Fantasie und Fuge a-Moll, BWV 561

Einige canonische Veränderungen über das Weihnachtslied:

Vom Himmel hoch, da komm’ ich her, BWV 769a

Concerto d-Moll, BWV 596

Ohne Tempobezeichnung

Grave

Fuga

Largo e spiccato

Ohne Tempobezeichnung

Fuge c-Moll, BWV 575

top of pageProgram 3: 9.00 Uhr

Toccata (Präludium) und Fuge F-Dur, BWV 540

Choralpartita “Christ, der du bist der helle Tag”, BWV 766

Concerto a-Moll, BWV 593

Ohne Tempobezeichnung

Adagio

Allegro

Fantasie C-Dur, BWV 570

Präludium und Fuge G-Dur, BWV 550

Präludium und Fuge a-Moll, BWV 543

top of pageProgram 4: 10.00 Uhr

Präludium und Fuge G-Dur, BWV 541

Choralbearbeitungen:

Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland, BWV 699

Herr Christ, der ein’ge Gottes-Sohn, BWV 698

Gelobet seist du, Jesu Christ, BWV 697

Wir Christenleut’, BWV 710

Ach Gott, vom Himmel sieh’ darein, BWV 741

An Wasserflüssen Babylon, BWV 653b

Wo soll ich fliehen hin, BWV 694

Wer nur den lieben Gott läßt walten, BWV 691

Ein’ feste Burg ist unser Gott, BWV 720

Trio-Sonate Es-Dur, BWV 525

Ohne Tempobezeichnung

Adagio

Allegro

Passacaglia c-Moll, BWV 582

top of pageProgramm 5: 11.00 Uhr

Fuge c-Moll über ein Thema von Giovanni Legrenzi, BWV 574

Choralbearbeitungen:

Vom Himmel hoch da komm’ ich her, BWV 700

In dulci jubilo, BWV 729

Jesus, meine Zuversicht, BWV 728

Liebster Jesu, wir sind hier, BWV 731

Nun freut euch, lieben Christen g’mein, BWV 734

Fuge h-Moll über ein Thema von Corelli, BWV 579

Präludium und Fuge C-Dur, BWV 547

Pastorale (Pastorella) F-Dur, BWV 590

Toccata und Fuge d-Moll (dorisch), BWV 538

top of pageProgramm 6: 12.00 Uhr

Präludium und Fuge a-Moll, BWV 551

Choralpartita “O Gott, du frommer Gott”, BWV 767

Trio G-Dur, BWV 1027a

Arie F-Dur, BWV 587

Allabreve D-Dur, BWV 589

Trio-Sonate G-Dur, BWV 530

Vivace

Lento

Allegro

Präludium und Fuge e-Moll, BWV 548

top of pageProgram 7: 13.00 Uhr

Orgelbüchlein (45 Choralbearbeitungen, BWV 599-644)

1. Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland

2. Gott, durch deine Güte

3. Herr Christ, der ein’ge Gottes-Sohn

4. Lob sei dem allmächtigen Gott

5. Puer natus in Bethlehem

6. Gelobet seist du, Jesu Christ

7. Der Tag, der ist so freudenreich

8. Vom Himmel hoch, da komm’ ich her

9. Vom Himmel kam der Engel Schar

10. In dulci jubilo

11. Lobt Gott, ihr Christen, allzugleich

12. Jesu, meine Freude

13. Christum wir sollen loben schon

14. Wir Christenleut’

15. Helft mir Gottes Güte preisen

16. Das alte Jahr vergangen ist

17. In dir ist Freude

18. Mit Fried’ und Freud’ ich fahr’ dahin

19. Herr Gott, nun schleuß den Himmel auf

20. O Lamm Gottes, unschuldig

21. Christe, du Lamm Gottes

22. Christus, der uns selig macht

23. Da Jesus an dem Kreuze stund

24. O Mensch, bewein’ dein’ Sünde groß

25. Wir danken dir, Herr Jesu Christ

26. Hilf Gott, daß mir’s gelinge

27. Christ lag in Todesbanden

28. Jesus Christus, unser Heiland

29. Christ ist erstanden

30. Erstanden ist der heil’ge Christ

31. Erschienen ist der herrliche Tag

32. Heut triumphieret Gottes Sohn

33. Komm, Gott Schöpfer, heiliger Geist

34. Herr Jesu Christ, dich zu uns wend’

35. Liebster Jesu, wir sind hier

36. Dies sind die heil’gen zehn Gebot’

37. Vater unser im Himmelreich

38. Durch Adams Fall ist ganz verderbt

39. Es ist das Heil uns kommen her

40. Ich ruf’ zu dir, Herr Jesu Christ

41. In dich hab’ ich gehoffet, Herr

42. Wenn wir in höchsten Nöten sein

43. Wer nur den lieben Gott läßt walten

44. Alle Menschen müssen sterben

45. Ach wie nichtig, ach wie flüchtig

top of pageProgram 8: 14.30 Uhr

Dritter Teil der Klavierübung (“Orgelmesse”)

Präludium Es-Dur, BWV 552, 1

Choralbearbeitungen, BWV 669-689:

Kyrie, Gott Vater in Ewigkeit

Christe, aller Welt Trost

Kyrie, Gott heiliger Geist

Kyrie, Gott Vater in Ewigkeit

Christe, aller Welt Trost

Kyrie, Gott heiliger Geist

Allein Gott in der Höh’ sei Ehr’

Allein Gott in der Höh’ sei Ehr’

Allein Gott in der Höh’ sei Ehr’

Dies sind die heil’gen zehn Gebot’

Dies sind die heil’gen zehn Gebot’

Wir glauben all’ an einen Gott

Wir glauben all’ an einen Gott

Vater unser im Himmelreich

Vater unser im Himmelreich

Christ, unser Herr, zum Jordan kam

Christ, unser Herr, zum Jordan kam

Aus tiefer Not schrei’ ich zu dir

Aus tiefer Not schrei’ ich zu dir

Jesus Christus unser Heiland

Jesus Christus unser Heiland

Fuge Es-Dur, BWV 552, 2

top of pageProgram 9: 16.00 Uhr

Acht kleine Präludien und Fugen, BWV 553-560

Präludium und Fuge C-Dur

Präludium und Fuge d-Moll

Präludium und Fuge e-Moll

Präludium und Fuge F-Dur

Präludium und Fuge G-Dur

Präludium und Fuge g-Moll

Präludium und Fuge a-Moll

Präludium und Fuge B-Dur

Trio-Sonate c-Moll, BWV 526

Vivace

Largo

Allegro

Fantasia und Imitatio h-Moll, BWV 563

Fantasie (Präludium) und Fuge g-Moll, BWV 542

top of pageProgram 10: 17.00 Uhr

Fantasie und Fuge c-Moll, BWV 537

Choralpartita “Ach, was soll ich Sünder machen?”, BWV 770

Präludium G-Dur, BWV 568

Fuge G-Dur, BWV 577

Trio-Sonate C-Dur, BWV 529

Allegro

Largo

Allegro

Präludium und Fuge h-Moll, BWV 544

top of pageProgram 11: 18.00 Uhr

Gottesdienst mit Musik von Johann Sebastian Bach

Präludium a-Moll, BWV 569

Sechs Choräle von verschiedener Art (Schübler-Choräle), BWV 645-650:

Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme

Wo soll ich fliehen hin

Wer nur den lieben Gott läßt walten

Meine Seele erhebet den Herren

Ach bleib’ bei uns, Herr Jesu Christ

Kommst du nun, Jesu, vom Himmel herunter

Toccata d-Moll, BWV 565

top of pageProgram 12: 19.30 Uhr

Präludium und Fuge c-Moll, BWV 549

Fuge G-Dur, BWV 576

Choralbearbeitungen:

Ach Gott und Herr, BWV 714

Allein Gott in der Höh’ sei Ehr’, BWV 717

Lob sei dem allmächt’gen Gott, BWV 704

Herr Gott, dich loben wir, BWV 725

Toccata (Präludium) und Fuge E-Dur, BWV 566

Choralbearbeitungen:

Der Tag, der ist so freudenreich, BWV 719

Erbarm’ dich mein, o Herre Gott, BWV 721

Herr Jesu Christ, dich zu uns wend’, BWV 726

In dich hab’ ich gehoffet, Herr, BWV 712

Concerto C-Dur, BWV 594

Ohne Tempobezeichnung

Recitativo. Adagio

Allegro

top of pageProgramm 13: 20.30 Uhr

Fuge g-Moll, BWV 578

Orgelchoräle der Neumeister-Sammlung, BWV 1090-1098

Wir Christenleut’

Das alte Jahr vergangen ist

Herr Gott, nun schleuß den Himmel auf

Herzliebster Jesu, was hast du verbrochen

O Jesu, wie ist dein Gestalt

O Lamm Gottes, unschuldig

Christe, der du bist Tag und Licht

Ehre sei dir, Christe, der du leidest Not

Wir glauben all an einen Gott

Trio G-Dur, BWV 586

Orgelchoräle der Neumeister-Sammlung, BWV 1099-1108

Aus tiefer Not schrei ich zu dir

Allein zu dir, Herr Jesu Christ

Durch Adams Fall ist ganz verderbt

Du Friedefürst, Herr Jesu Christ

Erhalt uns, Herr, bei deinem Wort

Wenn dich Unglück tut greifen an

Jesu, meine Freude

Gott ist mein Heil, mein Hilf und Trost

Jesu, meines Lebens Leben

Als Jesus Christus in der Nacht

Trio c-Moll, BWV 585

Orgelchoräle der Neumeister-Sammlung, BWV 1109-1120

Ach Gott, tu dich erbarmen

O Herre Gott, dein göttlich Wort

Nun lasset uns den Leib begrab’n

Christus, der ist mein Leben

Ich hab’ mein Sach’ Gott heimgestelt

Herr Jesu Christ, du höchstes Gut

Herzlich lieb hab’ ich dich, o Herr

Was Gott tut, das ist wohlgetan

Alle Menschen müssen sterben

Werde munter, mein Gemüte

Wie nach einer Wasserquelle

Christ, der du bist der helle Tag

top of pageProgram 14: 22.00 Uhr

Präludium und Fuge f-Moll, BWV 534

Choralbearbeitungen:

Gottes Sohn ist kommen/Gott, durch deine Güte, BWV 724

Vom Himmel hoch da komm’ ich her, BWV 701

Christum wir sollen loben schon, BWV 696

Herr Jesu Christ, dich zu uns wend’, BWV 709

Allein Gott in der Höh’ sei Ehr’, BWV 715

Fuga sopra il Magnificat, BWV 733

Concerto C-Dur, BWV 595

Trio d-Moll, BWV 583

Toccata (Toccata, Adagio und Fuge) C-Dur, BWV 564

Canzona, BWV 588

Präludium und Fuge D-Dur, BWV 532

top of pageProgramm 15: 23.00 Uhr

Präludium und Fuge e-Moll, BWV 533

Choralbearbeitungen:

Gelobet seist du, Jesu Christ, BWV 722

Vom Himmel hoch, da komm’ ich her, BWV 738

Vater unser im Himmelreich, BWV 737

Wie schön leuchtet der Morgenstern, BWV 739

Fuge G-Dur

Machs mit mir, Gott, nach deiner Güt, BWV 957

Trio-Sonate d-Moll, BWV 527

Andante

Adagio e dolce

Vivace

Fuge C-Dur, BWV 946

Präludium und Fuge A-Dur, BWV 536

Concerto G-Dur, BWV 592 Ohne Tempobezeichnung

Grave

Presto

Fantasie c-Moll, BWV 562

Fantasie G-Dur (Pièce d’Orgue), BWV 572

top of pageProgram 16: 24.00 Uhr

Achtzehn Choräle, BWV 651-667, 668a

Komm, heiliger Geist, Herre Gott

Komm, heiliger Geist, Herre Gott

An Wasserflüssen Babylon

Schmücke dich, o liebe Seele

Herr Jesu Christ, dich zu uns wend’

O Lamm Gottes, unschuldig

Nun danket alle Gott

Von Gott will ich nicht lassen

Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland

Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland

Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland

Allein Gott in der Höh’ sei Ehr’

Allein Gott in der Höh’ sei Ehr’

Allein Gott in der Höh’ sei Ehr’

Jesus Christus, unser Heiland

Jesus Christus, unser Heiland

Komm, Gott Schöpfer, heiliger Geist

Vor deinen Thron tret’ ich

About this performance:

| Für die Zusammenstellung der Programmfolge wurde W. Schmieders Thematisch-systematisches Verzeichnis der musikalischen Werke von Johann Sebastian Bach zugrunde gelegt. In das Programm sind alle Orgelwerke aufgenommen, die nachweislich von J. S. Bach komponiert wurden. Zusätzlich sind auch einige Kompositionen enthalten, bei denen es fraglich ist, ob hier Bach wirklich der Komponist ist. Nicht aufgenommen wurden diejenigen Werke, die unvollendet geblieben sind. Von den Werken, die in mehrere Versionen überliefert sind, wurde nur eine ausgewählt. Zwischen den einzelnen Programmen ist jeweils nur eine kurze Pause von ca. 3 – 5 Minuten geplant. Das Publikum wird während dieser Unterbrechungen um größtmögliche Ruhe gebeten, um die Aufmerksamkeit auf die Musik hin und die tontechnische Aufzeichnung nicht zu stören. Mit der Aufführung ist auch folgender Benefiz-Aspekt verbunden: Der finanzielle Erlös soll für die Weiterentwicklung der Orgelausbildung an der Russischen Gnessin Musikakademie in Moskau bestimmt sein. |

The programme of the complete cycle is based on Schmieder’s ‘Systematic Thematic Catalogue of the Musical Works of Johann Sebastian Bach’. All the organ works which demonstrably are by Bach are included in the programme. In addition there are some compositions over which some questions of Bach’s authorship are not settled. Of those works which have several variants, normally only one version has been chosen. Unfinished works of the composer have not been included. Between the individual programmes there will be a short pause of approximately 3 – 5 minutes. The audience is respectfully requested to remain as quiet as possible during the intervals in order to maintain the sense of deep reflection upon the music, and the entire concert is also being recorded. There is the further beneficial purpose to this performance, that its profits will be used to continue the development of the teaching of the organ at the Russian Gnessin’s Academy of Music in Moscow. |

| Alexander Fiseisky |

| Alexander Fiseisky wurde in Moskau geboren. Er studierte am Moskauer Konservatorium unter Professor Vera Gornostajewa Klavier und Orgel bei Professor Leonid Roisman. Seine weitere Ausbildung vervollkommnete er in Meisterklassen bei Wolfgang Schetelich, Leo Krämer, Daniel Roth und Jean Guillou. Alexander Fiseisky ist Solo-Organist der Moskauer Staatlichen Philharmonischen Gesellschaft und Leiter der Orgelklasse an der Russischen Gnessin Musikakademie. Eine beachtliche Anzahl von Kompositionen sind ihm gewidmet, wie z. B. die von Michael Kollontaj, Wladimir Rjabow, Milena Aroutjunova und Arif Mirsojew. Er hat an vielen bedeutenden Festivals sowohl in der ehemaligen Sowjetunion als auch im Ausland teilgenommen. Er betätigt sich als Jury-Mitglied bei nationalen als auch internationalen Orgelwettbewerben, wie z. B. beim Calgary Internationalen Orgel-Festival (Canada), dem St. Albans Internationalen Orgel-Festival (England) usw.. Durch Vorträge und Meisterklassen-Kurse an der Royal Academy of Music in London und dem Internationalen Orgel-Festival in Oundle (England), Musikhochschule Wien, Musikhochschule Hamburg, Peabody Conservatoire in Baltimore (USA) usw. erlangte er internationales Ansehen, sowohl als Tutor als auch als Musikwissenschaftler. Alexander Fiseisky hat viele Einspielungen gemacht, einschließlich des gesamten Orgelwerkes von J. S. Bach. Er ist ferner tätig als Sachverständiger in allen Orgelfragen seines Landes, organisierte zahlreiche Festivals und wissenschaftliche Konferenzen. Mit der Veröffentlichung einer Anthologie “Orgelmusik in Russland” im Bärenreiter-Verlag (8217-8219) ist er als Herausgeber sehr darum bemüht, das Beste aus der russischen Orgeltradition dem Westen zu vermitteln.

Born in Moscow, Alexander Fiseisky has become one of Russia’s premier and most influential organists. He studied piano at the Moscow State Conservatoire under Professor Vera Gornostajeva and organ under Professor Leonid Roizman. He had further guidance and masterclasses from Wolfgang Schetelich, Leo Krämer, Daniel Roth and Jean Guillou. Alexander Fiseisky is an official organ soloist of the Moscow State Philharmonic Society and Head of the Organ Class of the Russian Gnessin’s Academy of Music. A significant number of premières of works which he has given have been dedicated to him – including compositions by Mikhail Kollontay, Vladimir Ryabov, Milena Aroutjunova, and Arif Mirzoyev. He has performed at many of the major festivals in the former USSR and abroad. He regularly appears as a jury member of national and international organ competitions including Calgary International Organ Festival (Canada) and St. Albans International Organ Festival (UK), etc. His lectures and masterclasses at the Royal Academy of Music in London and Oundle International Organ Festival (UK), Musikhochschule Vienna (Austria), Musikhochschule Hamburg (Germany), Peabody Conservatoire in Baltimore (USA), etc., established his international reputation both as a tutor and musicologist. Alexander Fiseisky has many recordings to his credit, including the complete organ works of J. S. Bach. He also continues to be nationally involved in organ matters in Russia, organizing a number of festivals and scientific conferences. He is strongly advocating the introduction of the best of Russian organ tradition to the West by editing an Anthology of Russian Organ Music by Bärenreiter-Verlag (8217-8219). |

| The Organ of St Margareta Basilica |

| Um die Jahrhundertwende schuf die Firma Fabricius eine neue Orgel, die auf der Westempore Platz fand. Mitte der dreißiger Jahre wurde diese durch eine größere ersetzt. Nach dem Abriß der Empore gelangte diese Orgel 1957 in das südliche Querschiff. Mit Beginn der Restaurierungsarbeiten 1975 befand sich die Orgel in einem sehr schlechten Zustand und wurde ausgelagert. Eine Restaurierung wäre wiederum Flickwerk geworden, das nicht zu rechtfertigende Kosten verursacht hätte, so daß der einzige realistische Weg vorwärts war, eine neue Orgel zu bestellen. Die Auswahl des Orgelbaumeisters gelang relativ schnell, die Fa. Rieger aus Schwarzach in Österreich erhielt den Auftrag für ein Instrument mit 40 Registern auf 3 Manualen und Pedal. Zu langwierigen Auseinandersetzungen führte dann aber die Frage des Standortes der Orgel. Die Südwand wurde gewählt, und die damals gefundene Lösung bleibt – für jeden hörbar, der sich im mittleren und hinteren Bereich aufhält – akustisch gesehen ein Kompromiß, wenn wahrscheinlich auch der beste, der gefunden werden konnte. Die Fa. Rieger schuf ein Werk, das durch seine große klangliche Geschlossenheit, seine der schwierigen Akustik angepaßte dezente Kraft und seine Vielseitigkeit viele positive Beurteilungen erfahren hat. Durch die Verwendung erlesener Materialien und die an guten Traditionen orientierte Bauweise wird diese Orgel auf lange Sicht ihre Aufgaben in der Liturgie und in Konzerten erfüllen können. Diese Vielseitigkeit, die im Klang der Orgel deutlich hörbar wird, erlaubt es, stilistische Vielfalt zu pflegen und Musik mit unterschiedlichstem Hintergrund aufzuführen.

At the turn of the century Fabricius built a new organ in the church’s west end gallery. They considerably rebuilt it again in the mid-1930s, and after the demolition of the gallery the organ was removed to the south transept in 1957. By the start of restoration work in 1975 the organ was not only in a poor state but, being stored temporarily in an unsuitable place, such further damage was done as to render any further repair unjustifiable; the realistic way forward was to commission an entirely new organ. The choice of builder was made relatively quickly, Rieger of Schwarzach in Austria being commissioned for an instrument of 40 stops over three manuals and pedals. Somewhat longer deliberation was needed as to its position within the church. The south wall of the transept was chosen, and it is probably the best overall solution, and Rieger’s work, with its tonal unity, its ‘subtle strength’ suited to the difficult acoustic, and its versatility, was favourably received. Construction according to time honoured traditions, with materials of superior quality, ensures a long term ability to fulfil all that is required of it within both the liturgical and concert fields. This eclecticism, as the sound of the organ itself ringingly declares, allows the stylistic performance of music from many different backgrounds upon it.

Klaus Wallrath

| The Disposition: |

| Hauptwerk |

| 1. Pommer |

16′ |

| 2. Principal |

8′ |

| 3. Spitzflöte |

8′ |

| 4. Octav |

4′ |

| 5. Nachthorn |

4′ |

| 6. Superoctav |

2′ |

| 7. Mixtur V |

1 1/3′ |

| 8. Zimbel III |

1/2′ |

| 9. Cornet V |

8′ |

| 10. Trompete |

8′ |

| Rückpositiv |

| 11. Holzgedackt |

8′ |

| 12. Principal |

4′ |

| 13. Koppel |

4′ |

| 14. Gemshorn |

2′ |

| 15. Quintlein |

1 1/3′ |

| 16. Scharf IV |

1′ |

| 17. Rankett |

16′ |

| 18. Krummhorn |

8′ |

| Tremulant |

| Schwellwerk |

| 19. Bourdon |

8′ |

| 20. Salicional |

8′ |

| 21. Voix Celeste |

8′ |

| 22. Prestant |

4′ |

| 23. Rohrflöte |

4′ |

| 24. Nazard |

2 2/3′ |

| 25. Flöte |

2′ |

| 26. Tierce |

1 3/5′ |

| 27. Sifflet |

1′ |

| 28. Plein Jeu V |

2′ |

| 29. Basson |

16′ |

| 30. Hautbois |

8′ |

| 31. Clairon |

4′ |

| Tremulant |

| Pedal |

| 32. Principal |

16′ |

| 33. Subbaß |

16′ |

| 34. Octav |

8′ |

| 35. Gedackt |

8′ |

| 36. Choralbaß |

4′ |

| 37. Rohrschelle |

2′ |

| 38. Rauschpfeife IV |

2 2/3′ |

| 39. Posaune |

16′ |

| 40. Trompete |

8′ |

| Koppeln / Couplers: |

I/II, III/II, III/I, I/P, II/P, III/P6 Generalsetzer, jeweils 4 Werksetzer

Mechanische Spiel- und Registertraktur6 Generals, 4 Divisionals

Tracker action, mechanical stop action |

© Alexander Fiseisky

|

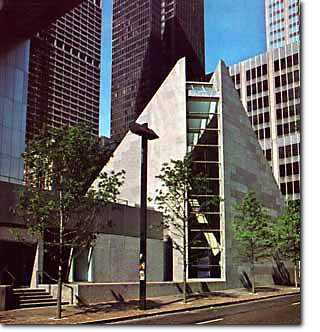

The minimalist modern architecture of St Peter’s was a perfect background for the highly spiritual music of Bach. Having never visited St Peter before, I was struck with it’s architect’s flight of imagination. I certainly have never seen a church where the sanctuary was below ground level, with ceiling windows facing the street. Several people were glued to the glass during the performance, and that created a feeling that the organ was speaking not only to us, sitting below, but also to the people outside, and to the sky, and to the entire city.

The minimalist modern architecture of St Peter’s was a perfect background for the highly spiritual music of Bach. Having never visited St Peter before, I was struck with it’s architect’s flight of imagination. I certainly have never seen a church where the sanctuary was below ground level, with ceiling windows facing the street. Several people were glued to the glass during the performance, and that created a feeling that the organ was speaking not only to us, sitting below, but also to the people outside, and to the sky, and to the entire city. BINGEN – It’s almost unbelievable: In spite of little advertising, even “unspectacular” organ concerts find their audience. Indeed, the listeners in the well-attended Catholic Church in Büdesheim were more than rewarded.

BINGEN – It’s almost unbelievable: In spite of little advertising, even “unspectacular” organ concerts find their audience. Indeed, the listeners in the well-attended Catholic Church in Büdesheim were more than rewarded.